We Herd Together, And Watch

In bearskin or t-shirt, people give anything for experiences together.

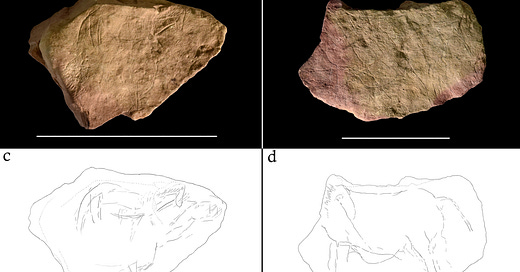

You are looking at some (very) vintage mixed-reality technology. These etched stones date from the Magdalenian Period, 11,000 to 17,000 years ago. In 2022 researchers figured out that these stones, originally from southern France and now on display at The British Museum, were likely placed around a fire. As the flames flickered, the animals etched on the rocks appeared to be moving. That’s entertainment!

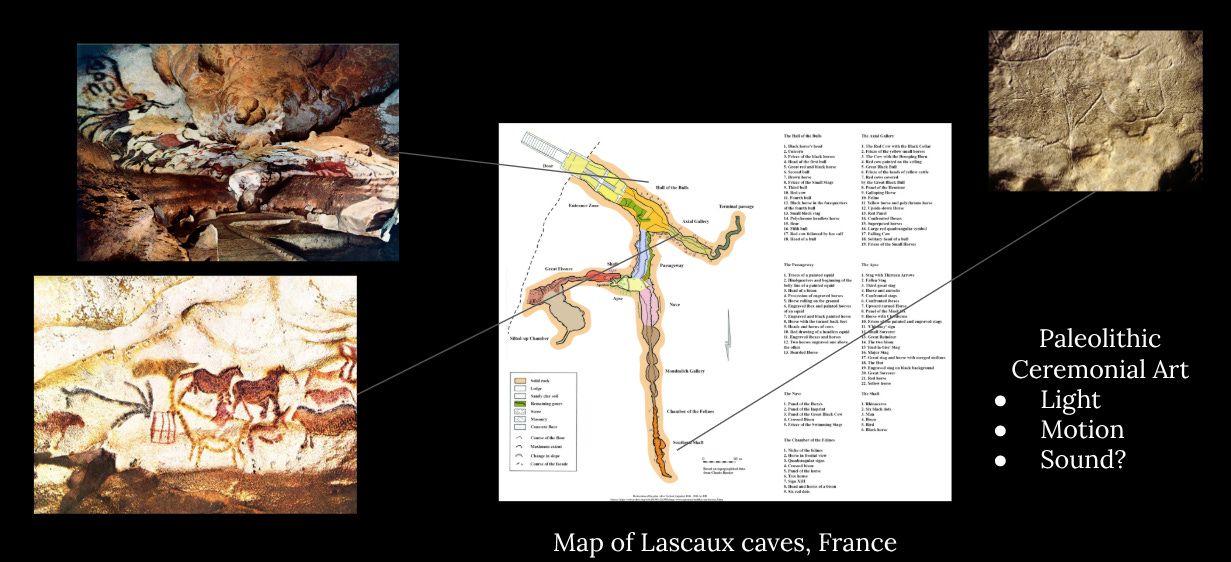

It wasn’t the only form of public interactive art known to cave people. About the same time, give or take 1000 years, entertainment technologists created a multimedia experience at the caves in nearby Lascaux. It’s likely that their audience proceeded through chambers with planned sequential decoration. Horses were drawn first, followed by aurochs (the extinct precursor of today’s cows), then stags; this procession follows the spring-summer-fall cycles of the animals’ respective periods of fertility. Visitors could go there and experience temporal and cosmic time, maybe relive some good hunting stories.

Added to this use of time, space, and motion, there could well have been sound, as percussion and flutes were also in use by then. Props, too: Besides tools for drawing, painting, and lighting, archaeologists have found decorative objects and antlers whose use is unknown. They’ve also found jewelry that used shells from hundreds of miles away.

Lascaux was hardly a one-off, a Las Vegas Sphere of its millennium. It was probably closer to a particularly successful theater, stadium, or megachurch. There seem to have been several such neolithic places to which people journeyed in order to be among other people, experiencing thrills, spectacle, or a little consideration of our place in the cosmos.

I have been to another cave, Rouffignac, where animals were painted along the curve of a dome in the wall, surrounding a deep shaft. Facing them on the dome is a lone human figure. Elsewhere in the cave, bison head towards each other from two sides of a cave depression, and there’s a goat whose eye is made from a piece of crystal protruding from the cave wall.

We rode a little electric train perhaps a quarter mile to get back to these paintings. To effect a mood, the guide momentarily turned out the lights; there’s something timeless about darkness so complete that it feels solid. When the lights come on again you find yourself in a far-off space.

The guide pointed out something that astonished me. “You never see cross-out marks on cave paintings.” Maybe they had light under-drawings, but whoever did the final lines and color clearly had expert hands. The creator(s) had investigated the caves, thought about the shapes of the stones and what might go on them, and then likely practiced the work they eventually executed on the walls, for some ritual or entertainment purpose.

That takes lots of skill and time, suggesting that cave people had divisions of labor. Their art was valuable enough that others were out hunting and gathering, so that these specialists could focus on their work. Similarly, the shell jewelry at Lascaux suggests a similar labor division; a system of trade is much easier to envision than an individual walking a few hundred miles in order to assemble personal adornment.

To me this early specialization of work is one of the most astonishing things about cave paintings. The human urge to gather with others and experience something together, which drove this specialization, turns out to be one of the oldest and most profound traits of the species.1

Today we have digital life, where we can virtually witness or participate in a thousand different movies, games, or events, all without encountering a single other person in the flesh. If anything, this “advance” may have actually driven up the price of experiencing a treasured cultural moment together. Streaming music and live video is basically free, but Lady Gaga’s August show at Madison Square Garden has good seats for $2400. Ticketmaster estimates next winter’s Superbowl will have tickets on resale for between $4000 and $6000. You won’t see the game as well as you might at home, but you’ll be cheering alongside other fans.

It’s also notable how quickly big entertainments, public and private, go away when they’re no longer culturally relevant. At the turn of the last century, stereoscopes, the optical devices that create 3D photographic images from two slightly different 2D images, were standard entertainment gear in middle class households. Distributors in New York and London stocked over 500,000 different views of ruins, monuments, famous people, and barnyard jokes, among other fare. After radio and TV were invented, the stereoscope largely disappeared; it has a vestigial presence as a collector’s item.2

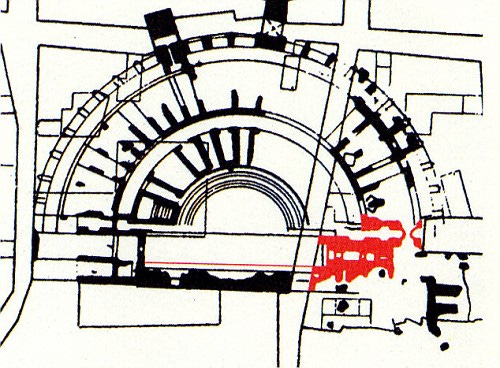

Theater itself disappeared for a time in the early Middle Ages, possibly because it became unsafe to congregate anywhere except in churches. You can see the evidence in Naples, Italy, where there’s a neighborhood with a few odd curves in the streets, and stone benches raked in levels against apartments. It’s all part of a long-vanished Roman Theater, complete with backstage changing rooms and corridors for actors to make surprise entrances.

Roman entertainment included tragedies and comedies, but also jugglers, mimes, obscene songs, taunts of the audience, parodies of the rich and powerful, and other crowd pleasers. It’s recorded that Emperor Nero once delivered a poetry recitation at the Naples theater when an earthquake struck. Thinking this was a sign of delight from the gods, he made the audience stay in place while he finished. Which was probably pretty awkward.

These light performances existed alongside the big time entertainments of gladiatorial combat, animal fights, mock battles, and other sporty delights, that were held in other venues. They’ve found over 230 of these gladiatorial locales over the empire, which over centuries gave diversion to millions of people.

And then, poof. Typically the public entertainments had been sponsored by local bigwigs, giving ordinary people a taste of the exotic and powerful. When the Roman wars turned from conquest and wealth extraction to costly defense, the Imperial powers started debasing the currency and the funding for entertainment dried up. A few urban venues hung in there, supporting the perennially popular clowns and physical marvels, but there was little left by the time the Church, in 692, banned Roman theater.3

Not that the church didn’t engender its own kind of theater, influencing great painters and modern drama, along with some astonishing riots and public burnings. Those entertainments are for another day.

Another astonishing thing is how little the styles and subject matter change over thousands of years. Living as we do in a culture where artistic styles, schools, and characters shift multiple times in a decade (which is good for the art market), it seems almost unbearable that the same groove lasted for millennia.

There was also the American Chautaqua Movement, which thrived from about 1880 to the 1920s. Its outdoor talks and entertainments, sometimes attracting thousands of spectators, with everything from lectures on Shakespeare to vaudeville comedy, were designed to entertain and elevate ordinary people. At the peak of the movement there were some 12,000 of these gatherings in the U.S., before it nearly died out in the face of mass media and cars. It’s recently been enjoying something of a comeback - Salman Rushdie’s near-fatal attack took place at the original Chautaqua Institution - though now the movement is said to be in turmoil. We also now have TED talks, which you can watch in real time, though some wealthy people prefer to attend in person, at an admission price of $6,250 to $25,000 (if your application is accepted.)

Along with forbidding law students in Constantinople to dress in the style of Goths or Armenians, as decreed by the buzz-killing Council of Trullo. Standards!