The New Class: Future 2.0, Eternal Beta

They're running the country. Here's how they see things, and why.

On Thursday I wrote about the rise of a new global class. Some of its wealthiest and most eminent people are now directly involved in, or have acceded to, reshaping the most powerful nation in history.

Ten years ago many of them wanted to leave the nation-state for sovereign artificial islands in international waters, a bitcoin-fueled Internet, the Metaverse, or maybe a nice civilization on Mars. A future separate from America.

Instead of that original vision, Future 1.0, they are working on Future 2.0, where they remake America in accordance with how they think the world should work.

This move makes a lot of sense, not simply because it’s better to stay here, a largely functional place, than move to some libertarian fantasy. They’re treading a familiar historical path that opens up when people develop new technologies, powerful enough to change how they see the world and themselves. Those who steer these new technologies and the systems they create then use them to modify the existing systems of power.

Our new tech is presented as if it’s without precedent, but that’s not correct. Some things change, but the deep patterns stretching over centuries are very familiar. Often the sequence doesn’t go as planned, though.

Let’s get some context.

What history teaches, and withholds

From 2005 to 2015 I lectured at U.C. Berkeley’s School of Information Studies.1 The basic thesis of my course was extrapolated from Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities,” one of the most delightful academic books I’ve ever read.2

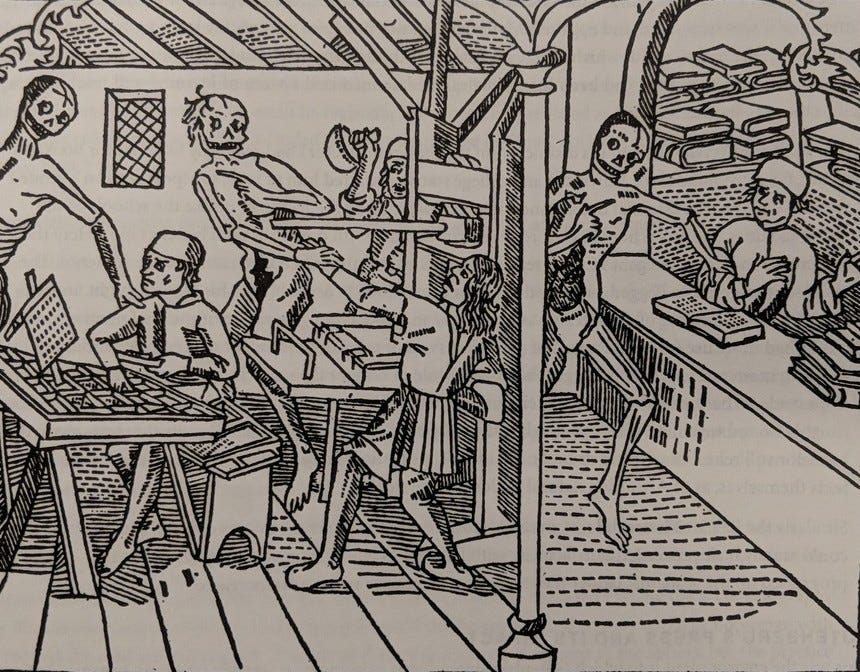

Subtitled “Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism,” the book posits (oversimplification alert!) that a powerful media technology, the printing press, dramatically reshaped the world’s political order. The change came not simply from print and its related technologies, but from print’s interaction with the market, a dimension not usually covered by media theorists like Marshall McLuhan.

Starting in Europe, not only was there a rapid explosion of books and learning, there was a sudden abundance of books in vernacular languages, as opposed to the Latin, Greek and Hebrew dominant in manuscripts.3

Language-consciousness in the market was a big deal on several levels. It gave people with leisure an incentive to learn to read, since that no longer involved learning a whole new language. It vastly increased demand for books; book piracy in vernaculars came early and fast.

And, fatefully, God started speaking like normal people.

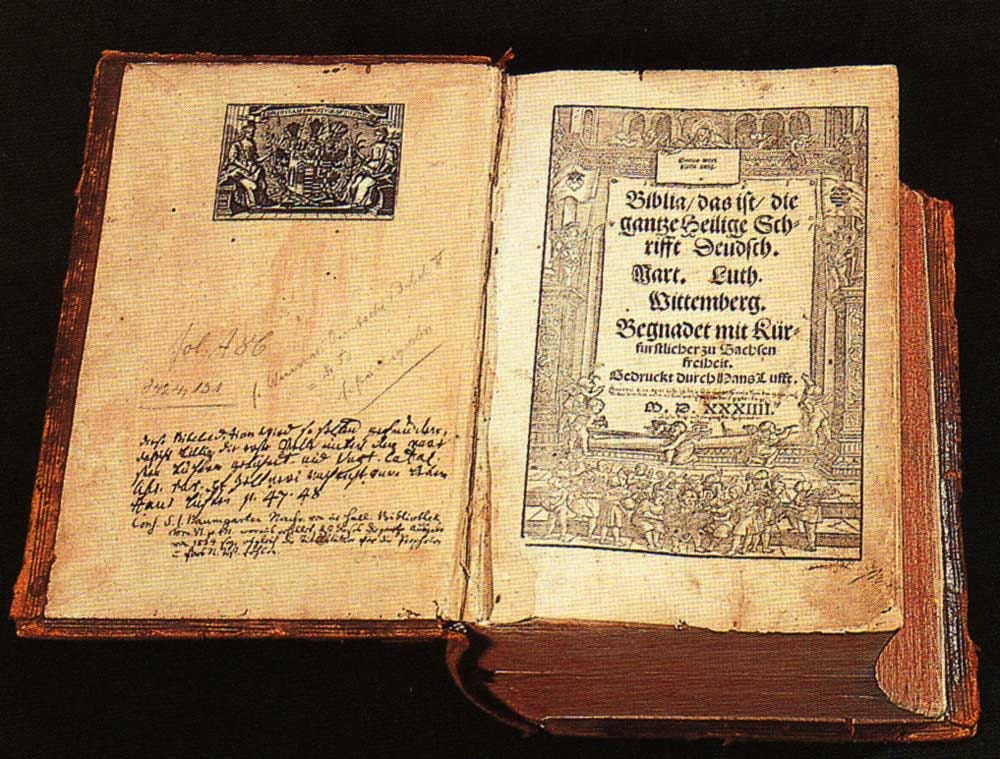

Martin Luther translated the Bible into German in 1522, five years after he kicked off the Protestant Reformation with his widely-reprinted criticisms of the church.4 Vernacular bibles and anti-church writings had appeared before, but since they were manuscripts, their spread were easily controlled. By comparison, print was unmanageable. Soon God was speaking in French and English, among other vernacular languages.

Unintended consequences

Anderson notes two dimensions of this: First, people experienced a powerful psychological effect from hearing God speak their own language, which both strengthened the Protestant argument against the need for an mediating priest, and raised the status of the vernaculars, since God spoke in them. This changed the social epistemology, or people’s sense of how the world was put together.

Second, the vernacular boom in bibles and ordinary books helped consolidate languages. You can’t print a separate edition for every village and dialect as, say, French speakers transition across Burgundy and the Great East into German speakers. You consolidate and standardize.

Once you’ve established a more common language, the one that God speaks, you start a powerful nationalistic myth: We are French speakers, being a French speaker is an interesting thing, we have always been French speakers, People who don’t speak French are different.

All that from the printing press, and nobody saw it coming. Thanks, technology! Have at it, markets!

Plus, it was the start of a process that created our society without teleology, a place where process is the goal.

Let’s grow this idea.

I started to look for parallels to Anderson’s idea in other powerful communication technologies, searching for ways they affected the political order. It turns out that the parallels are legion:

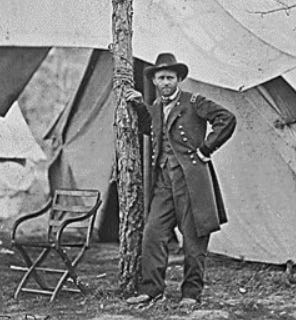

Photography upended painting, gave us the ordinary, and caused social reform by capturing reality. I wrote about Impressionist painters contending with this new technology. That wasn’t the only change: Relatively portable cameras made it possible to shoot people in natural situations. At the start of the Civil War, generals and men stood to stiff attention, and by the end you had Grant slouching against a tree. Seeing real people, in command and amid the carnage, changed how we understand war.

The immigration industry boomed, because people could send home photos of themselves doing well in the New World. As the technology improved, social reformers like Jacob Riis photographed slums and child labor, causing new labor and hygiene regulation. Hogarth’s etchings of slums never did that.

Telegraphy, rotogravure, and the culture of speed. Communication became increasingly fast, and instantaneous became the expected norm. You can find writers complaining about the new intensity as far back as “The House of the Seven Gables” in 1851. New urban society got a culture of mass-production newspapers and magazines that changed the cadence of “news” towards something more relentless. Journalists had to create stories they built on constantly, and politicians cooperated. We began to see film stars5 arise as news makers. As early as Calvin Coolidge, they came to the White House for photo ops.

Smart politicians learned to use technology to meet their needs. Compare how Adolph Hitler used radio (recorded in a stadium, with a crowd screaming, since fascism is fundamentally about the self disappearing into the crowd) with Franklin Roosevelt’s approach (his “Fireside chats” made it feel like the president was sitting across from you in the living room, befitting a middle-class democracy.) Same tech, entirely different effects. There are lots of other examples involving television, film and PR, a bigger subject for some other time.6

Where today’s technology is going.

Just as speed of production mattered for the press, portability of machines mattered for photography, or staging of a speech mattered for radio, so today our new technology has influenced the thinking of its creators in ways that are at play in the current doings in Washington:

Launch fast and figure stuff out; software is cheap. Think how many products Google has launched and then killed, once they didn’t make a profit. Or how new hires at Facebook were encouraged to touch core code on their first day at work. Or how smartphones and automobiles leave the showroom and then change, via over-the-air updates and apps.

The outcome is that, in a sense, the products people interact with are in a permanent beta version, always contingent, and capable of change, depending on what their controllers learn.

Everything can be recapitulated in software. The software-intensive nature of this tech makes it the first mass media technology to recapitulate and combine so many disparate things. It’s a camera and a tape recorder, it’s a broadcast service. It’s a newspaper, it’s a production studio. It’s a data log, it’s a data analysis machine, taking the next action automatically. And now it’s a disembodied robot, virtual or physical, engendering real consequences in peace and war.

All work is a learning loop. Failure is a value. One thing about STEM7 is that learning typically involves more instances of being wrong and then improving than people in the Humanities and Social Sciences are used to. The tech is not particularly harder, it just takes longer to learn. A lot of the Valley’s success is due to people recognizing that failure is learning, as long as you fail in the right way. That thinking extends to company building and products.

Data collection is critical and secrecy is a big deal. Even a failed launch tells online companies a lot about what people do and don’t like, and how the systems performed. Therefore it’s vital to collect and analyze as much data as possible. This was true even before the LLMs of generative AI made all data potentially valuable, but now it’s critical.

Many companies learned this lesson early. In 2006 AOL released some of its Web search query logs to the public, supposedly stripped of personally identifiable information. Very quickly privacy advocates found people anyway, by triangulating the data. Over at Google, I’ve been told, they were able to use that data to approximate AOL’s costs and undercut them in selling ads. That experience taught people that anything you release can be used in ways you don’t expect.

You can see how these values resonate,

as we see a secretive, seat of the pants, data-hungry cohort move with blistering speed through the Federal Government. They’re in Permanent Beta. It will be interesting to see what real inefficiencies they can spot and correct with their data-intensive software, and what they can code to replace government processes.

The real test will be how well that holds up in a system that isn’t made out of software, but humans, millions of whom count on a reliable delivery of checks and medicine. In this environment, you can’t just launch, then fix.

But the new crowd may also be evaluating the consequences of failure somewhat differently than governments have in the past, treating it as learning as they move forward. We’ll see how that works out.

The other revolutions I described took place over decades and centuries. For us, much is yet to come, particularly as this new technology affects everyone’s view of the world.

As with all the other revolutions, predicting what’s next is a chancy thing. One person’s passions clash with another’s necessity, and it’s hard to discern the outcome. Multiply that by a million people and situations, and the only working theory is Chaos, where a small change has an outsized consequence.

The first lesson of history is, Lessons only take you so far. Sooner or later, Reality gonna reality.

It was formerly the Library Sciences school, and is now the iSchool. The dean in those days, the estimable Anno Saxenian, was very good about bringing in outside lecturers, to the sometime consternation of the academic lifers, but it made for a good mix. I shared an office with Mitch Kapor, a venture investor, founder of Lotus software, and cofounder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation; and Hal Varian, an economics professor working as Google’s chief economist. It was daunting company. I was there to provide some contemporary media/journalism perspective.

It has one of the surest markers of a great academic book - you can read the footnotes on their own and be entertained.

Pre-print writers like Dante and Boccaccio had elevated the Tuscan language by writing in the vernacular, but the idea of Tuscan Italian as a full-blown tongue to be used widely only came after the printing press, with figures like Pietro Bembo and his father deserving of their own story.

The Reformation started when Luther got upset at the number of indulgences (think of them as “get out of Hell” cards) the Vatican was selling to pay down its debts. The Pope, Leo X, son of Lorenzo de’ Medici, shared his father’s taste in hiring expensive artists. When you see that beautiful Vatican, all those Raphaels, you know who to blame for the split in the church.

In his 1962 classic, “The Image,” Daniel Boorstin coined the term “pseudo-event,” described celebrities as people being famous for being famous, and wrote a great analysis of how politicians like Joseph McCarthy played the press by abusing its standards and needs. Lots of this is still fresh.

It became pretty clear that Anderson was on to more than he knew. So was John Culkin, who when writing of McCluhan notably said “We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.” It’s true for all tools, but we make sense of the world from information - and it turns out that the way we get it creates not just how we see the world, but our political expectations.

Science, Technology, Engineering and Math. All that stuff they say we should be teaching more, often as an excuse for cutting music and civics classes.