Myths, Maintenance, Momwork.

In a complex world, we cling to single-hero guy stories. What a disaster.

Everybody is indicting everything possible: This or that election, the old administration, the new administration, the price of eggs, this meme, that photo of the guy that did the thing. Above all, the System, man. Along with the indictments, there is pervasive anger that people aren’t pissed off enough about the thing that’s pissing us off.

On the assumption that “everybody” is never right, this makes it a great time to cut in the other direction, and praise the hard work of building and sustaining order. Such praise feels subversive enough in these times to warrant its own challenging name: Momwork.

As we’re about to see, it’s something damn critical for how well our world runs.

Momwork and its discontents

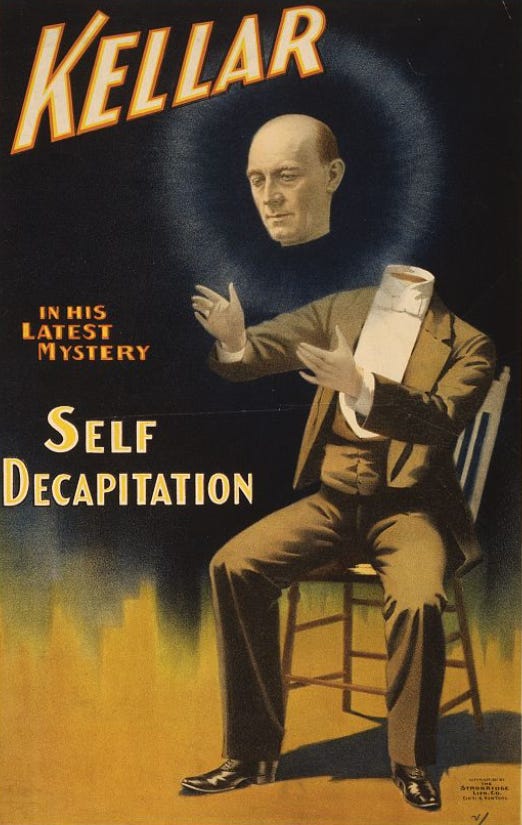

If this intentionally gendered term, “Momwork,” bothers you, please keep reading. It’s there for a point, to counter the absurd degree to which we gender, reward, and fetishize the disruptor, the rule breaker, the mythic lone visionary who we now tell ourselves is the one who advances The Human Project.

Momwork, in contrast, requires socializing and sustaining, maintaining and growing healthy systems. It’s done by men and women both, in the same way that both men and women possess the “masculine energy” recently championed by one of our billionaires.

The term is chosen in order to shock. “Momwork” sounds awkward because of how we’ve come to think about the work done by mothers, and by extension, others who organize and maintain the world.

This notion is baked into the culture. When we talk about the American frontier, we champion the Cowboy, the Mountain Man and the Marshall. These discontented lone wolves supposedly put their stamp on a blank place. When they’re done killing “hostiles,” though, it’s the male and female strangers who learn to get along with each other, doing the low-glory work of town councils, libraries, and schools. If you’re building a nation, those collectives make a greater difference than another guy with a gun.

But that guy is still the hero. When we talk about the government, particularly the current government, it’s the rule-breaking leader who gets the attention, not the thousands and millions of low paid, low-glory men and women who see to it that there is an orderly process to operations. In business, it's all about the visionary disruptor, not the operations person who sees to it that the disruption works, creating a sustained and growing money-making company.

The supposedly masculine energy of disruption is cool. Momwork, the feminine energy behind the maintenance of things, consists of many more things, but cool isn’t one of them. It doesn’t pay as much (or in the case of real moms, it doesn’t pay at all.) It doesn’t lend itself to myth-making as easily. It’s a lot tougher, more complex, and requires more attention.

So it needs champions. I’d be happy to see Momwork adopted by its practitioners, negative connotations and all, in the same way “gay” was turned on its head for homosexual rights, or police officers may refer to themselves using the once-derogatory term “cops.”

After all, there’s a good chance we’re about to see what happens when Momwork ebbs, and the world is nothing but disruptors.

The return of masculine energy (as if it ever went away)

I started thinking about Momwork1 after Mark Zuckerberg’s recent podcast with Joe Rogan. Zuckerberg talked about his jiujitsu hobby, and how it had attuned him to the “masculine energy” of a bout with his buddies. This elided into a perceived lack of said energy in the modern workplace.

“There's something (about) the kind of masculine energy (that) is good,” he said. “Society has plenty of that, but corporate culture was really trying to get away from it….having a culture that celebrates aggression a bit more has its own merits that are really positive…we kind of swung culturally to that part of the spectrum where (the workplace is) all like, ‘Masculinity is toxic. We have to get rid of it completely.’”2

A couple of obvious howlers here can be set aside quickly. Zuckerberg is a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu blue belt, which is no small thing. But there are many, many women with black belts in the sport who could thrash him and his male friends. Worse, “toxic masculinity,” is an entirely different thing from masculinity, just as “rabid dog” is different from “dog.” Plenty of companies allow dogs in the office, but draw the line at dogs with rabies. And as someone who has spent time in scores of companies, as a reporter, an employee, and a consultant, I assure you that few have a low inventory of competitiveness and aggression, traits Zuckerberg associated with masculinity. Certainly, I’ve seen no lack in tech.

The more troubling reality is that Zuckerberg, most other tech visionaries, and the public, think tech billionaires could occupy their exalted perches without the feminine energy, the Momwork, of others, who make order from their chaos. They continue to think of their success along highly gendered masculine lines. It makes for a good story you can tell in a flash, since it has a single actor and a supposed decisiveness.

But equally important to invention, maybe more, are the supposedly feminine traits of establishing order, building a sustainable corporate culture, ensuring that growth is backed by repeatable processes, and communicating effectively, both internally and externally. That’s how employees, customers, and investors know what the new thing is, how to work with it, and how they can make it grow. Sheryl Sandberg, who tamed the chaos at Facebook and built its advertising-based business, is only one of several examples.

Without those “feminine” traits? A lone guy with a vision, a rule breaker, here to disrupt?

That’s the crazy dude on the bus. Something, basically, you can find at a lot of startups that fail, because no one built a coherent system.

Let’s dig into what makes the difference, and how we got here.

Complex world, linear male stories

You don’t usually hear about tech company leadership in terms of broad partnerships, in part because (brace yourself) women’s stories don’t get told as often as men’s. Same goes for masculine-energy angles versus feminine-energy ones.

Moreover, multi-character stories are tougher to pull off in the press, particularly in our short-attention-span world, where readers have been schooled to think every CEO, from Wall Street to a grocery chain, is an irreplaceable god, each worth every million of their pay package.

Just below the surface, though, it’s just as often about partnerships at the top, particularly in tech.

When we hear about these, it’s usually in two versions of “masculine” energies, the lone nerd and the garrulous salesman. Think Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs. Bill Hewlett and David Packard. Even at this male level, that dispenses with this “lone genius” thing.

Going deeper, the involvement of women and their “feminine” energy is arguably one of the reasons that the United States grabbed the global lead in tech. Other countries, including China, held women back from participating. Their companies are typically marked by poor sustained innovation and negative working cultures. Many governments are now investing in women to try to reverse that trend so they can tap into the talents of their entire population.3

So why don’t women get their due? Besides Sandberg, there’s Susan Wojcicki, who gave Larry Page and Sergey Brin Google’s first home, led its marketing, told them to buy YouTube, and turned it into a global colossus. Also at Google, Megan Smith acquired Maps and strengthened a rapidly-growing engineering team, before leaving to be America’s first Chief Technology Officer. Fei-Fei Li is revered as an AI pioneer for creating and fostering Image Net, the online database that kick started today’s Artificial Intelligence revolution.

For 30 years, Mary Meeker has been explaining the Internet and its companies to investors and journalists. Patricia Stonesifer led Microsoft’s consumer products and helped Bill and Melinda Gates set up their foundation, establishing the standard for tech philanthropy. Elsewhere at Microsoft, Melissa Waggener and Pamela Edstrom’s independent public relations firm has been telling Microsoft’s story since 1984.

While we’re on the subject of PR, you only know about the masculine energy of Marc Benioff’s Salesforce, Marc Andreessen’s VC firm, Meta, Apple, Alphabet, and countless other firms, because women have been creating and telling the story, while erasing themselves (that’s the job of PR.)

That’s a lot of Momwork (which, again, guys do too, in the same way women invent stuff, run companies, and kick butt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.) Momwork sees that people are literally and figuratively fed, clothed at their desks in a way the world recognizes as healthy. It lays down the basics, from reading to behaving in groups, so you feel like there’s a structure to this chaotic world. With a good story that people want to share, with a few basic rules, people don’t have to be so scared, and can work together for the long haul.

Momwork instills organizational and social skills. Without them, we’d probably still be living in trees and throwing poop at each other.

It’s Momwork all the way down

Just try living without Momwork. You’ll get Facemash, Zuckerberg’s project in which unattractive Harvard guys could judge the sexual attractiveness of unknowing Harvard women. It was shut down after a couple of days, and in Congressional testimony Zuckerberg called it a “prank.” I don’t know what he now says about his early business card, which said, “I’m CEO, bitch.”

I do know that once Facebook got venture capital, one of the first things they did was to bring on some seasoned older engineers, who understood how to keep large complex computer systems running. Facebook beat its rival, Friendster, because Facebook didn’t go down as often. In other words, it won on engineering Momwork.

There’s still a bias against this kind of work in tech. The so called “dev/ops” that runs modern software is divided into heroic developers building cool new stuff and faceless operations people who just keep it running. Developers have to push out products, and any problems or mistakes they leave unresolved are termed “technical debt,” a thankless task for someone to clean up later.

Google has notoriously launched visionary products, only to “deprecate” (i.e. stop supporting, and turn off) them if they don’t make money, attract enough attention, or meet strategic goals. All vision, no Momwork. That’s fine, sort of, since the stuff was free to begin with. But what happens when we deprecate things outside of tech, and where the stakes are higher?

Hating as politics, and our national Momwork gamble

When you consider modern political phenomena of every stripe, from Al-Qaeda to Brexit, from Occupy Wall Street to first-round MAGA, a striking theme emerges: Almost all are propelled by saying “No!” to something, whether it’s the absence of a fundamentalist Ummah, leaving the European Union, getting rid of big banks, or hating Obama. It’s all negative disruption, with some sense that after the disruption things will simply be better.

When these succeed, most of the time none of the winners really has a plan beyond their promises. They are low-Momwork programs, you might say.

Building things is harder than breaking them, of course, and hating on things is easier than working to improve something over time. Online media are generally poor at creating long-term building, possibly because there are too many voices, and there’s a certainty in condemning, compared to finding a framework for collaboration.4

Here, it seems, we go again.

I mentioned the incoherence in Zuckerberg’s praise of masculine energy. What he really seemed to mean came out later in the talk with Rogan, when Meta’s leader praised America’s new president. “One of the things I’m optimistic about with President Trump is,” Zuckerberg said, “He just wants America to win.” On the face of it, this is either banal or absurd – have we had presidents who didn’t want America to win?

Going deeper, and considering Zuckerberg’s comments about pernicious European regulation, and Mr. Trump’s “never surrender” tutelage under attorney Roy Cohn, Zuckerberg seems to mean “wants America to win in places where the rules hold it back.” Win overseas despite the rules, which would be novel for an American president. Skip the Momwork of international order, and say you want Greenland.

Meta and many other companies are abolishing rules around DEI, and setting up a new order based more on top-down dictates. Like the new administration, they just want to win. Washington and much of the media are tightly wound up in the myth of a single leader overseeing all, from the heads of various agencies to the president himself.

The first week of the administration was rich with rule-breaking executive orders, rather than the slow process of law making. It culminated late Friday with the dismissal of several Inspectors General, the people who ensure that the rules are transparent and obeyed. Which sounds a lot like the celebration of The One Man, and the eclipse of Momwork-type maintenance.

It will be interesting to see how that goes at the Department of Defense, where about 3 million workers (and 2 million retirees) are now under a single highly opinionated individual. Or the Department of Health and Human Services, where $1.7 trillion in mandatory spending and $130 billion in discretionary spending are under another visionary rule breaker.

And of course, in the Oval Office itself, where during the president’s previous administration there was a lot more turnover and bickering among personalities than there was useful and positive Momwork. An early indicator is the president saying “No!” to illegal migrants, with no plan for who will pick America’s crops or do its lowest-paid construction jobs.

The (hopeful) future of Momwork

If history is a useful guide, we’re probably not looking at an irreversible catastrophe here. It’s more likely to be a colossal screw up. And who knows, I could be wrong about the whole thing, and the relentless rule of decisive visionaries replete with masculine energy will be an utter success, Momwork be damned. I’ve certainly been wrong before.

My best scenario is that, if the masculine energy messes up, we start to credit the people who order systems and keep things running. Michael Lewis was something of a prophet of this in The Fifth Risk, his book about the difficulties the previous Trump administration had when “shaking up the system” ran into “keeping this thing running, lives depend on it.”

This September, technology futurist Stewart Brand will publish the first in his series on Maintenance, which he sees as core to the way the world works. Much of what he’s saying, judging from the early releases, will be richer and more fully developed investigations of what I’ve called Momwork. He’ll probably do a better job of making it heroic, too - his story of the first ‘round the world yacht race, and the centrality of maintenance, is a fantastic, possibly life-changing read.

If we’re very lucky, we’ll come out on the other side of this season of wrongheaded ideas about masculine energy with a new appreciation of each other, tending to the small things, and building lasting and beneficial systems.

You know, ___work.

Big shout to my friend, the writer Nell Scovell, with whom I had the conversation that engendered the term Momwork. Among her other illustrious career highlights, Nell is the cowriter, along with Sheryl Sandberg, of Lean In, the bestseller challenging women to be more assertive at home and in the workplace. We worked together briefly on an early draft of this piece. I take full responsibility for all errors and blow back.

Here’s a longer excerpt from the Zuckerberg talk. Like many people, he converses in a somewhat haphazard way, with lots of “likes” and repetitions, which I’ve cleaned up out of respect for what he’s saying:

”There's something (about) the kind of masculine energy (that) is good. Society has plenty of that, but corporate culture was really trying to get away from it. And I think these forms of energy are good, and I think having a culture that, like, celebrates aggression a bit more has its own merits that are really positive. And that's been a positive experience for me. Just, like, having a thing that I can do with my guy friends and we just beat each other a bit. It is good.

“Part of the intent on all these things is good. If you're a woman going into a company, it probably feels like it's too masculine. It's like there isn't enough of the kind of the energy that that that you may naturally have, and it probably feels like there are all these things that are set up that are biased against you. And that's not good either because you want women to be able to succeed, and have companies that can unlock all the value from having great people no matter, you know, what their background or gender.

“But I think these things can all always go a little far. And I think it's one thing to say we want to be welcoming and make a good environment for everyone, and another to say that masculinity is bad. And I just think we kind of swung culturally to that part of the spectrum where it's all like, “Masculinity is toxic. We have to get rid of it completely.”

“Both of these things are good. You want feminine energy. You want masculine energy. You're gonna have parts of society that have more of one or the other. I think that that's all good. But I do think corporate culture sort of had swung towards being this somewhat more neutered thing. And I didn't really feel that until I got involved in martial arts, which I think is still a much more masculine culture. And, so and not not that it doesn't try to be inclusive in its own way, but, but I think that there's just a lot more of that energy there. And I just kind of realized it's like, oh, this like how you become successful at martial arts. You have to be at least somewhat aggressive.

“There are a few of these things throughout your life where you have an experience, and you're like, “Where has this been my whole life?” And it just turned on, like, a part of my brain, a piece of the puzzle that should've been there, and I'm glad it now is.

“That I felt that way when I started hunting.”

You can also see the full interview, raw, here.

Thanks to Nell for this point.

Two interesting exceptions are Wikipedia and open source software, which are sustained by a distributed network of contributors. In both cases, a basic framework is commonly understood and respected by the participants, without a lot of process deviation, and no one gets rich or powerful from the process itself.

I was expecting Sheryl Sandberg in feminine-tech-pantheon (but of course, you didn't need to include them all, just she's the low-hanging in the pantheon).

I've been in and around tech most of my life (because I'm a bay area native, and because I know of a lot of folks in tech). The values you're hearing about now, loud and publicly, were always there, and none of this new-post-election tech-speak is at all surprising (to me).