Like many of you, I have a past. I’ve fallen through ice and contracted pneumonia. Following horseplay, I spent two months in a wheelchair. I was stranded on a cliff face near a 700-foot drop. A teenage boy once put a knife to my neck, removing the blade in exchange for my watch. I’ve been in car wrecks, on a plane that lost an engine, lived in a house with poor gun hygiene,1 and walked on hot coals. And that’s just the stuff I’m copping to here. For the most part, I figured, this survivable wreckage was the freight one pays for living here, sometimes thoughtlessly.

Last August, though, I finally went too far. Without considering the ramifications, I coughed.

Stupid, right?

Jolts went down both arms, and my hands instantly went numb and tingled. They’ve been like that ever since. It’s like wearing lightly electrified gloves underneath my fingers. This makes typing weird, and hurts my balance and dexterity. As it spreads to my feet and legs, it intimates worse may arrive.

Which is why, by the time you read this, a very capable man will have made a two-inch incision in my neck, pushed aside some pliant innards, and snaked through to my backbone a viewing tube and a pneumatic drill. The drill is for cutting and grinding. A small plate will have been fitted on the vertebrae.2 Then my surgeon will have removed his tools and sewn me up, leaving me ready for a few days of pain killers and classic films.

That’s a little scary to think about, and I couldn’t be happier.3 I marvel at the medical miracles I’m experiencing. I’m going to the hospital in the morning and I’ll be back in time for a late lunch! That said, I struggle with that age-old mortal companion, absolute dread in the face of the infinite unknown, in ways our ancestors both knew and could never have known.

But first, the miracles. My complaint was first inspected with X-rays. A bunch of electrons were precisely accelerated onto a piece of tungsten, initiating braking radiation that was aimed at the top of my spine. That didn’t yield enough information, so in late October I lay in this big tube while powerful magnets aligned all the hydrogen atoms in me, so a radio signal could then flip some of them. When those tiny guys flipped back, the MRI showed the action in tissues deep within me.

Using basically all of human history for comparison, we are unimaginably blessed by our scientific advances.

But as always, new knowledge has its discontents. “This,” my neurosurgeon said, tapping the moving watery image of two vertebrae compressed and squeezing out the disk sandwiched between them. As I write “this,” the disk is pressing against my spinal cord, almost certainly a result of that reckless cough. Reader, I saw this in motion on a screen in the doctor’s office.

To fully appreciate what seeing that was like, imagine Gene Simmons’ tongue oppressing my spinal cord, the precious bundle which carries all messages and instructions between my brain and the rest of me.4 I very much wanted that errant thing seen to.

This. The disc. That thing. The moment a body part, even something that earlier last summer was a respected part of me, goes rogue, it becomes a non-Quentin thing. We don’t like to consider the reality that we are towers of wet meat, filled with trillions of different living things fulfilling all sorts of purposes as best they can in the moment. We want to be solid, singular, and the same over time. I am reminded of the way our brains constantly rewrite our memories so their travelogues of our internal trip through space and time stay more logical and coherent.

“Can you make it go back in?” I asked the doctor about my Gene Simmons imitator.

“When we can do that, we’ll get the Nobel prize,” he said.5 I was briefly disappointed. When you live among medical miracles you come to expect them. Working around technology, where the next greatest thing ever has always just been invented, doesn’t help.

The doctor did offer a couple more things to try, including a course of steroids, but it seemed pretty clear he wanted to go in through the front of me, and soon. “Normally we’d schedule this for February or March,” he said, “but let’s try and do it before Christmas.” For which I heard: “If I could, I’d lay you on the floor right now with a magnifying glass and a penknife; this thing is going sideways, fast.” What your doctors don't say to you matters almost as much as what they do. Two weeks later I got the go-ahead from my medical insurer,6 and 12 days ago I got my date.

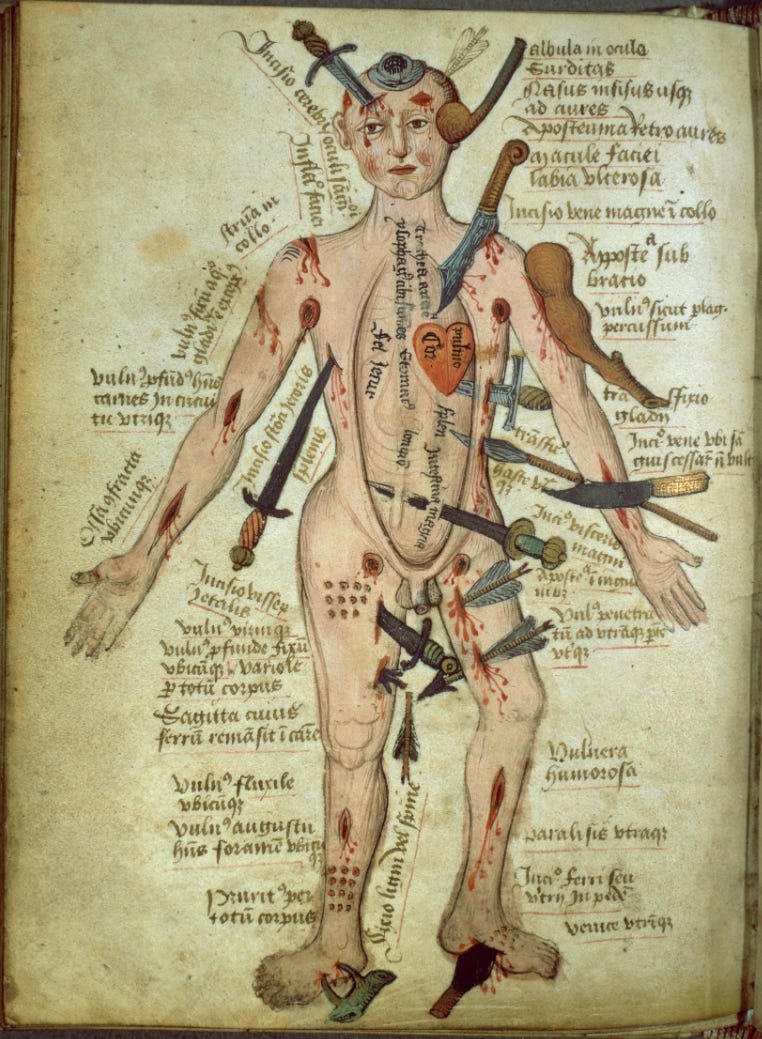

Since then I’ve been thinking about how the age-old terrors of weakness, injury and ultimately mortality work on us now. For most of human history the solid-feeling body met its last reckless moment in mystery and resignation. Now there is hyper awareness, new measurements and new understandings about symptoms, syndromes, protein spikes, folded proteins, etiologies, etc. More names for additional things in an ever more complex system we’re are still learning, which makes us keen to understand even more. And with every new name, there’s the suggestion of a corrective action we might take. A hope, at least.

And there are expectations of more to come, of greater certainty and power. If they can line up all my hydrogen atoms, they can probably reverse time on my disk popping out, right? When that’s done, there’s some stem cell thing we can do so I grow better vertebrae, right? Maybe in a couple of years some tiny robots will swim around inside, keeping Quentin, Inc., in fighting trim, right? Right?

All that may indeed be coming, right. Yet in our continually insistent expectation we can reach the wrong conclusions.

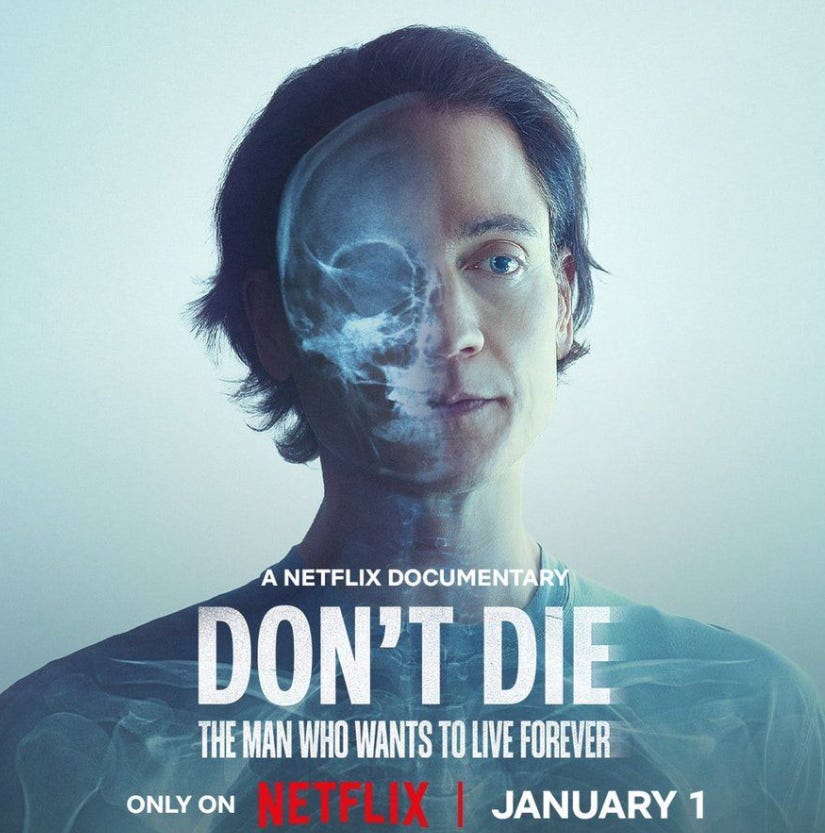

For the most part, we are not simply content to think that we’re lucky to be here, now; our need to understand and manipulate can make us feel entitled to so much more. Some carry this kind of thinking even further. Aubrey de Grey, a British biomedical gerontologist, holds that aging and death are just defects, engineering problems that can be solved. Bryan Johnson, an inventor and VC, pushes a regimen designed to end dying (and hosts a “Don’t Die Summit” in cities around the country, at up to $1500 a ticket.)7

It’s true that tech, in particular medical technology, really does do many amazing things. It has helped us live longer, getting more people to the limits of how long a human body can live, and it will potentially shorten the so-called “sickspan,” when an aging person spends time in painful terminal decline. But it is likely that death itself is, indeed, a feature of life, and not a bug. Nature seems more interested in generations of life changing within an ever-changing environment.

There’s no sign that any tech can change the deep fundamentals, including the mortal dread that is part of the miracle of consciousness. That is of course timeless. And while medical technology has changed much, one thing hasn’t changed: we love our cleverness, and only wish it would take us farther.

In an earlier post I quoted a few lines from Antigone, written 2,465 years ago, about man’s cleverness and our fate:

“he hath resource for all; without resource he meets nothing that must come: only against Death shall he call for aid in vain…”

I can’t decide if that’s a tragic observation, or a comic one. For certain, even then they knew something about the current age.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a date at the movies. Over 3,000 titles from around the world, beamed wirelessly to my tablet computer. Seems like a miracle.

I was sitting a cabin offshore of Sitka, Alaska. Its owner had wanted his children to know that guns are always dangerous, so he kept 13 rifles and a long-nosed .357 magnum revolver fully loaded, with a round in each of the rifles’ chambers. There was a bullet hole in the fridge, from that time a guest hadn’t been informed of this unique tutoring. The owner also dumped all the extra bullets for his guns in a large cardboard box, all mixed together, next to the kerosene heater. You should have seen his look of scorn when I moved the box and organized the bullets on my first day there.

I asked if it could be seasonally engraved with a reindeer or a snowman, but that service is not available. Yet. I like to think I give people good business ideas.

There’s the joy of never having this condition, of course. If “bad things not happening” brought happiness, right now I’d be delirious about not stepping on a fer-de-lance, or being the target of an asteroid, or any of the other horrors not currently underway.

The image is nauseating by design, to convey some of the urgency I quickly gained for a surgery. Previous to this essay I tested it on a half-dozen people, including a dear friend who was once kicked into a senseless heap by some hookers late at night in Jakarta. Universal success. Gene has that effect on people.

Never ask these guys about challenges like Reversing What Time Has Done To The Body in November. The Nobel Prizes are announced in October, and they probably don’t start getting psyched for the next ones until April or so.

Yes, from that insurer, itself a medical miracle.

I may be wrong in the idea that Mr. Johnson cannot cheat death, and if so I will die when he does not. I console myself that in the year 2500 I won’t have to listen to a smug 523 year-old rich person telling me he was right.

just got outof 20 day stint athospital. appreciativeof your appreciation; don't know whenI will be remotely thesame.

Excellent column, Quentin, and I appreciated the marginalia (endnotes). I look forward to reading more of your posts. Thanks