An acquaintance at a well-known tech company was telling me about the frustrations of their poor public perception. The company discussed in the press is unrecognizable to those on the inside, a disconnect that goes beyond the usual mismatch between generalist journalists and engineering-minded employees.

The response to public criticism from this company’s communications side is often hostile.1 It’s like the way officials of the current administration get on Sunday talk shows and start answering questions by slamming the press, except that kind of aggression stokes their political supporters. There’s little upside for hostility from the tech world.

“How’s your documentation?” I asked.

A hard smile. “Judging from our customers, it’s terrible.”

That was telling.

Software documentation describes a company’s product, from the goals it seeks to accomplish to the means by which it does it, with accompanying text, illustrations and videos. It’s written mostly for customers who will develop and deploy the software, but it’s also used internally by new hires and third parties trying to figure out the product they will be working on. It’s like a user’s manual.

There are many kinds of user’s manuals. A recipe book is a user’s manual for making food, and doesn’t usually require a description of intention. Much of literature is akin to a user’s manual for the world, an entertaining way to wise people up to how their society works. This is particularly true when society is going through big changes: Baldassare Castiglione’s “Book of the Courtier” of 1528 described the makeup of a Renaissance gentleman, and for the rest of that century it was influential in bringing humanist education and values to the courts of Europe. In the early 18th century Daniel Defoe wrote novels like “Colonel Jack” to describe the new social fluidity of a world in which a person might occupy many positions in a single life.2 Charles Dickens prospered by moving readers through the societies of an industrializing and rapidly-expanding London. Today Science Fiction has given us the words and realities of “cyberspace” and “the metaverse,” picking up early on the dominant cultural force of the age. Blueprints, maps, timetables - they’re all documenting something, for their specific audience.

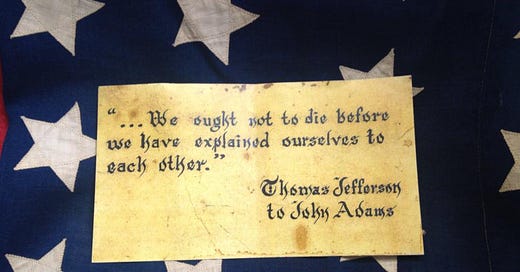

Often technical documentation has elements of support, like Q&As about different aspects of the product. Good documentation often has the unusual aspect of addressing why programmers made the choices they did. It includes descriptions of why the product’s creators invented or elected to use various routines and frameworks, elucidating the thinking behind their choices. Documentation which expresses intention often exposes the customer to some of a company’s values and choices, since it’s saying why it made a particular choice, when many other choices were possible. As such, documentation can also be seen as a window into a corporate culture. How well does this company explain itself, in terms of its products?3

Hence the reason for my question about the quality of the company’s documentation. Whether it’s easy to understand and welcoming, or difficult to parse or aloof and alienating, can tell you much about how its creators feel about themselves.

I was associated with a company with notoriously poor documentation. The main reason for this was that, in their early days, they were building out a technology so advanced that it had few commercial parallels. This had the dual effect of making employees feel like a tribe who were creating something very special that the rest of the world didn’t know about, and going very light on the documentation of their internal product. Why bother, since only fellow employees had to figure it out?

The idea was to hire exceptionally bright people, and have them stare at the core technology for a long period, personally figuring out its capabilities by talking with people and getting involved hands-on. Since they were smart, motivated, and surrounded by people who felt like they were on a mission, building something the world had never seen before, it worked well. People became true believers in the guts of the product, to an almost cultish degree. No knock on them there - many great companies and institutions are a little like cults.4

When the rest of the world caught up with this company, they decided to sell aspects of what had been their proprietary technology. Proper documentation became a problem. They struggled for years to create a user’s manual that strangers to the cult could use.

It was often hard to explain choices made long before, and they found little glory in trying to turn the choices of the cult into something “ordinary” people could understand. Worse, they tended to talk down to customers, effectively telling them that they’d be stupid not to use what was clearly the superior technology they’d created. Empathizing with lesser mortals was not a big part of the skill set.

Novels and recipes don’t have this problem. They’re assumed to be for just about everybody, so their creators have an interest in making their work easily accessible. Technical documentation, particularly for products new to the mainstream, can come with trappings of the strange new culture that created it, one that was successful in part because it was insular. People at these companies also have a habit of empathizing with each other more than with the outer world, developing their own language and rituals around work.5

Which gets to the reason for my question. Poor documentation was a possible sign that the company was proudly insular. And, like many cultures, when it was questioned by the “normies” of the popular press, there was a bias toward hostility, and the emotional pain that comes with being misunderstood. So, they lash out.

This is a hard thing to change, but an excellent thing to be aware of.

It’s not rational, or particularly helpful, but we’re talking about people here, and no one should accuse people of 100% rationality. We’ve all acted that way at one time or another, particularly when the necessary beliefs and structures of our lives are called into question.

Who ever wants to tear up their own user’s manual? Or perhaps, even read it the way an outsider might?

This is not unique to tech. I had a friend who worked in PR at Disney, where he learned the phrase “cut off their oxygen.”

The full title of “Colonel Jack” is

“The History and Remarkable Life of the truly Honourable Col. Jacque, commonly call'd Col. Jack, who was Born a Gentleman, put 'Prentice to a Pick−Pocket, was Six and Twenty Years a Thief, and then Kidnapp'd to Virginia, Came back a Merchant; was Five times married to Four Whores; went into the Wars, behav'd bravely, got Preferment, was made Colonel of a Regiment, came over, and fled with the Chevalier, is still abroad compleating a Life of Wonders, and resolves to dye a General.”

Which gives you a pretty good sense of the plot.

Intention is a big deal in programming, since things change so fast. As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago in a piece on technical debt, programmers looking at old code ask themselves “what was this person thinking?” about as often as they think of getting more coffee. Charles Simonyi, who came out of the legendary Xerox PARC computer research center to give Microsoft its graphical user interface and lead the Applications group, spent 16 years trying to build a company around “intentional software,” which would resolve this issue. He couldn’t make a practical version.

No knock on great companies to say they’re also like cults, with secret languages and rituals. At the old Motorola, run for three generations by a family named Galvin, someone who’d been there for seven years was said to be “galvinized.” Two years after I joined The New York Times, where for many years a fully-established person was said to be “a Times man,” I was told by my editor, “you just got here.” Google, of course, described an ideal employee or product as being “googlely,” a term no one could quite identify, but included attributes like clever, positive, and playful.

Sometimes with threatening reinforcement. I don’t know the current policy, but for many years at Amazon, new hires saw their options vest beginning at their second anniversary, instead of the standard one year. That meant the company had a lower risk if they didn’t properly acculturate the new person.

Yes, 'Google Cloud Platform' has a horrible, contradictory, incomplete, full of sediment rocks of idiocy of hundreds of thousands of 'engineers' who left a long time ago... documentation. But I always thought that it's because they poached the 'cloud' group from Oracle, who brought the culture of behaving as arrogant p...cks with them as a free addition to their experience and expertise... from _that_other_ company. I promised myself 3 or 4 years ago, that I will _never_ pay a single penny for GCP ever again. Haven't violated the oath until this day.

FIVE TIMES MARRIED TO FOUR WHORES