“Greg, it’s a dynamiters' convention,” I said to my boss. “In Idaho. Trust me, I’ll find something.”

This is a story about my best day in the old world of journalism, before online life upended what people read, the way they read it, how news outlets made money, and thus how reporters figured out and executed their stories. At least, how I did.

Thus, it is a story from a different world. This isn’t a better/worse comparison, but a tale designed to illuminate some of the changed working realities in the journalism business over what seems to its writer like a pretty brief time. I’m the third generation in newspapers, newsletters, and magazines on both sides of my family, and nothing has affected the business like this. Which alone makes it noteworthy. Plus, I participated in exceptional destruction for this tale, from which you may also benefit.

My best day in journalism began a couple of months after I was talking with my boss. But really, that’s where it started. We were at The Wall Street Journal’s San Francisco bureau. Officially I was writing about wireless technology, cell phones and satellites, but effectively I was writing as many strange stories from across the American West as I could find. These would go in the center column of the day’s paper, providing Journal readers with a welcome break from dutiful reading about the bond market, mergers & acquisitions, department stores, or perhaps even cellular telephone technology and satellites.(1)

I developed my specialty in such features when I was with the Journal in Tokyo, ostensibly covering the collapse of the world’s second-largest financial system, but also writing about Godzilla movies, and the town in Japan where Jesus lived for many decades after he escaped crucifixion(2).

For someone of my inclinations, joining The Journal’s San Francisco bureau felt like joining the majors. There was a breathtaking roster of excellent feature writers, and we enjoyed each other’s work like no place else I’ve earned pay. I’d done well in my first couple years in San Francisco, with stories about a Canadian’s plan to flood the U.S. with weed (he did, but served four years at the federal in Atlanta) or Nevada’s state-sponsored 200 mph amateur road race (along with the boar hunting and reindeer aphrodisiac stories discussed in the hunting museum story.)

My track record enabled my bureau chief, the late Greg Hill, to blink and then smile at the prospect of explaining this outlay to management. Northern Idaho was an area known for survivalist cults and general weirdness (3), and on pure spec I was proposing to spend three days with all types of high-explosive specialists and the people who love them, witness their competitive fireworks show, tour the show floor to discern what was new in managed physical catastrophe, and otherwise find a story worth the cost. Always seek a boss with an appetite for annoying their bosses. It was a gamble, but something I could work between stories about this new global satellite project.

God, I miss the budgets newspapers had then.

Before journalism went online, newspapers had on average twice the profit margins of the Fortune 500. With a finite number of outlets and slower reading habits, the competition was still fierce, but it was less about having the hottest take on the newest thing, and more about giving readers something they wouldn’t find elsewhere (and there was no fear that it wouldn’t immediately be skinned to any number of outlets, destroying its ephemeral value.) (4)

Today all of the action is in digital, so that’s where the reporting is. Which is great, since there’s so much there to read (and high multiples of takes of varying quality on whatever the news just was.) It does mean people are at their desks a lot more, looking at the Internet in various ways. In Sandpoint, near Coeur d’Alene, it was about looking at people and listening and hoping something would turn up. As it turned out, feeling and smelling too.

Though there was much to gawk at, it was low budget affair. The after dinner presentation was a U.S. Forest Service employee’s slideshow on his specialty, blowing up abandoned, undocumented, mines. The American West is full of them, nobody knows how many or where. It began about about 150 years ago, when our honored forebears, many of them deep into Civil War PTSD, scoured America’s vast and glorious Western landscape for whatever they could chop down, shoot, or tear from the ground, selling it fast and leaving plenty of mess when done. “Cleanup” didn’t matter much to folks who were wandering lonely through what seemed like infinite space. This went on in some places until about a century ago.

In the case of hard rock mining, the leavings in their shafts came to make home to rattlesnakes, bears, mountain lions, and poisonous spiders. There were innocuous puddles that were actually 100’ holes into which heavily polluted water had been dripping for a century - a careless hiker’s boots might instantly fill, drowning them in poison. There were cave ins, and old dynamite, which over the decades ages gently into something like highly unstable nitroglycerin.

He had lots of lurid closeups of these things on the screen, usually lit by his headlamp. With each new and vivid hazard I sensed growing fear and anxiety moving through his burly audience like a riptide. You could feel a shift in the room, and smell the anxiety. If he was shaking up people who sometimes lost fingers as a condition of work, I figured, I was smelling a story.

These unknown mines are what’s known as an “attractive hazard,” killing the unwary adventurers who find them. When after his talk I pitched The Forest Service guy about doing a follow-along story about his work, he figured I could help warn readers about the danger. (5) It didn’t hurt that he was a fellow writer, coauthor of what remains one of our more memorable government documents, “Obliterating Animal Carcasses With Explosives.” A useful tutorial on how trails in Yellowstone stay so neat after a hard winter.

I returned to San Francisco. Greg was good with the story. As it happened there was a mine needing closure in just a month or so, about 100 miles south of Coeur d’Alene. I could fly back to Spokane, then drive an hour to participate in the initial inspection tour. This was a necessary step, since the mines also sometimes housed endangered species of bats, and their habitat was sacrosanct. (If there were any bats, other men would weld big bars across the entrance.) If everything worked out, I then could fly back up to Spokane, rent a car again, and witness the demolition.

God, I miss budgets.

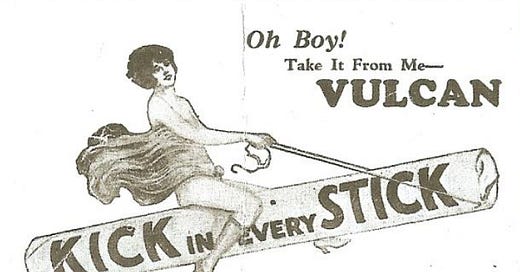

The Wall Street Journal, now owned by Rupert Murdoch, may still own the boots, helmet, and headlamp I procured. Thus equipped, I met my guide at the site. We pushed a century of cobwebs out of our way, and walked a mile inside the hand-cut hard rock shaft, ten by ten feet, searching for hazards and bats. My God, but people had to work hard. Not 200 yards in there was a niche holding three cases of rotting dynamite; the slogan, “A kick in every stick” was still legible on the wood, but oozing from it rotting sides was a gray mass of highly volatile explosive. More sticks were plugged into walls as we proceeded, their fuses like the tails of rodents stuck and oozing in mid-getaway. Whoever worked here left in a hurry.

We walked slowly to the end of the level part, then turned off our headlamps. The absence of light was like a solid, like inarguable black loneliness or a mute god. My companion threw a pebble down a hole dug there. It echoed for 30 seconds before finding rest.

No bats, though. There would be destruction, so I was in great shape, story wise. This initial walking tour of the mine would be the spine of the story, on which I could hang the strangeness of this work, the history, and the physical sensations during the journey. I wrote all that up while waiting for the paperwork required to seal shut the mine to clear. Back at the office my cell phone and satellite stories were picking up, and I busied myself with an upcoming international conference in Rome.

Word came down that we were clear to blow the mine shut, my kicker for the story. My best day in the old world of journalism began with a flight to Spokane with all my macho mining gear, plus some nice dress shoes and a suit in the luggage. Inside the mine, I had one of the more heart-in-throat moments of my life, as the government man delicately placed fresh charges on a cubic yard of rotting TNT. We clambered above the adit, and he yelled “Fire in the hole.”

The long mine became the barrel of a giant blunderbuss, boulders and dirt blowing from its muzzle, knocking down trees and clouding the air with hard rock dust. The boom echoed through us and the hills, surrounding everything and reverberating for longer than I could understand. In one instant he’d created in the mountain a demon’s roaring mouth, then it was silent forever.

I got back in my rental and just barely made it to Spokane in time for the flight to Seattle. There, I changed out of my hiking boots and into business attire. I called in the last paragraphs to San Francisco, got a final read on the story, and picked up my flight to Rome, where my satellite conference was beginning. I landed in Italy and made it into town, taking notes on satellites in a hotel conference room, still feeling the demon-mouthed mountain and perfumed lightly with dynamite.

My best day in journalism ended at the base of Rome’s Spanish Steps. I and some satellite people watched dozens of Italian kids, all obsessed with their new digital phones, jabbering away and short messaging each other nonstop with a new texting feature.

Cheaper. Faster. Ephemeral. Habit forming. Those telecom execs saw a glittering future. (6)

“Look at them,” a PR guy for the conference said, “they’d rather have their phones than eat.”

He was right, and if I could have seen what else those phones were signaling, I’d have known that my best day in journalism, marked by money enough and time to poke around and find a good tale to tell, had reached its end.

(1) No kidding, these stories were a real gift for some people, to a point where they’d save them to read on the commute home. Sometimes when I published a feature I liked, I’d wander up and down BART, watching people read my story. I could see from their expressions when they’d got to a particularly good part. There’s no experience like that in writing now, and it’s too bad.

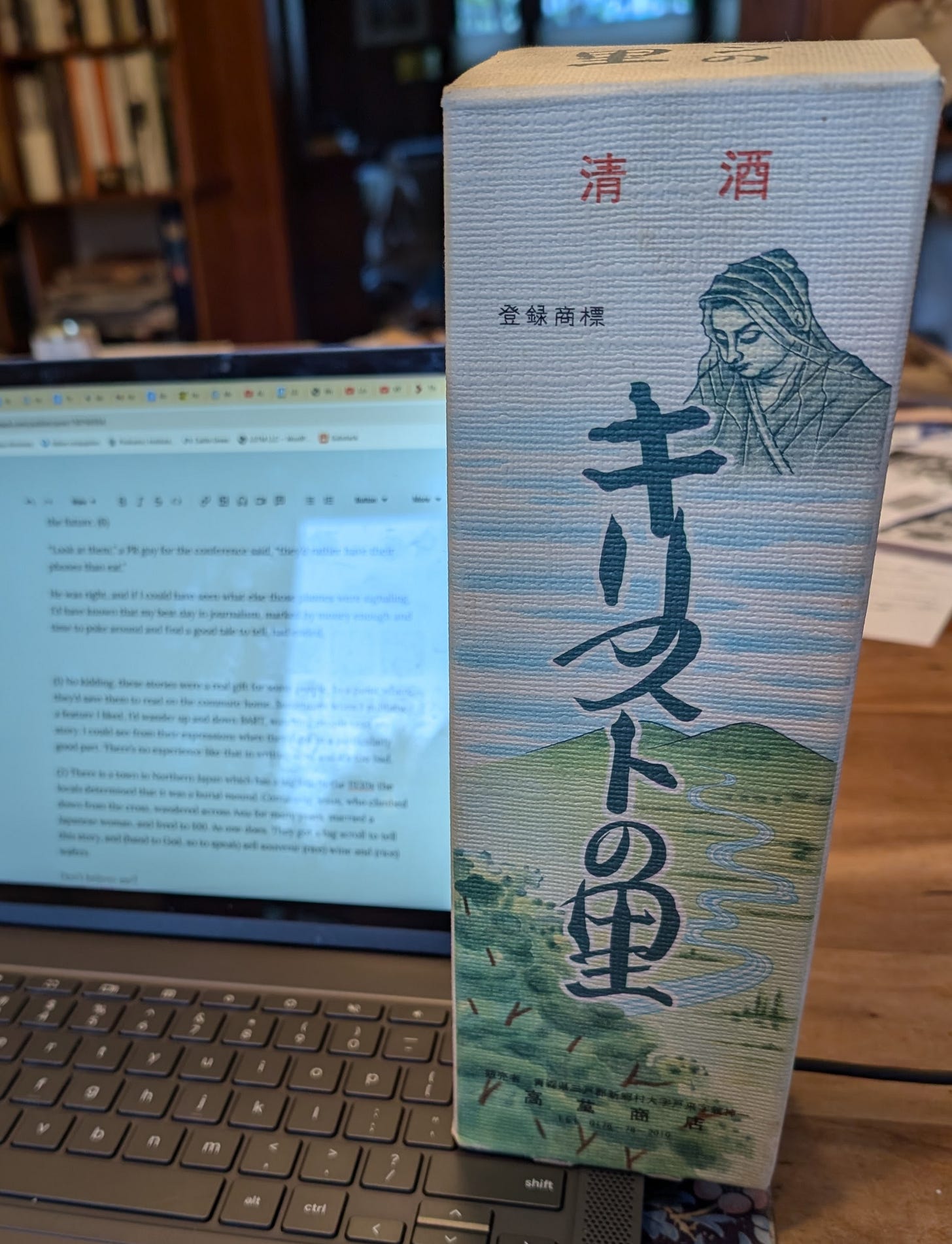

(2) There is a town in Northern Japan which has a big hill. In the 1930s the locals determined that it was a burial mound. Containing Jesus, who climbed down from the cross, wandered across Asia for many years, married a Japanese woman, and lived to 100. As one does. They got a big scroll to tell this story, and (hand to God, so to speak) sell souvenir (rice) wine and (rice) wafers.

Don’t believe me?

(3) In a world beset with change, it’s good to know that some things have stayed the same.

(4) Budgets were even bigger at LIFE in my father’s time there. Someone decided to do a photo spread on condors, and they sent a guy to the Andes for two months for a spread of perfect shots. In fairness, the photographer, John Dominis, was exceptional - you can see more of his work here.

(5) He may have been right in that world, but not in this one. In researching this I found there is now a YouTube channel where amateurs wander these deathtraps. Clicks!

(6) The satellite project was Iridium, which turned into a $5 billion fiasco with the Internet bubble, but enabled Elon to create Space X. A story for another time.

QH — beautiful piece. I felt like I was beside you as you retold your best day as a journalist. I adored your extended meditation on how the world has turned since then, without regurgitating platitudes.

Bless the travel budget that allowed you to have this one-of-a-kind experience.

You remind us all that the word blunderbuss is sadly underused. Such a good piece. Thank you.